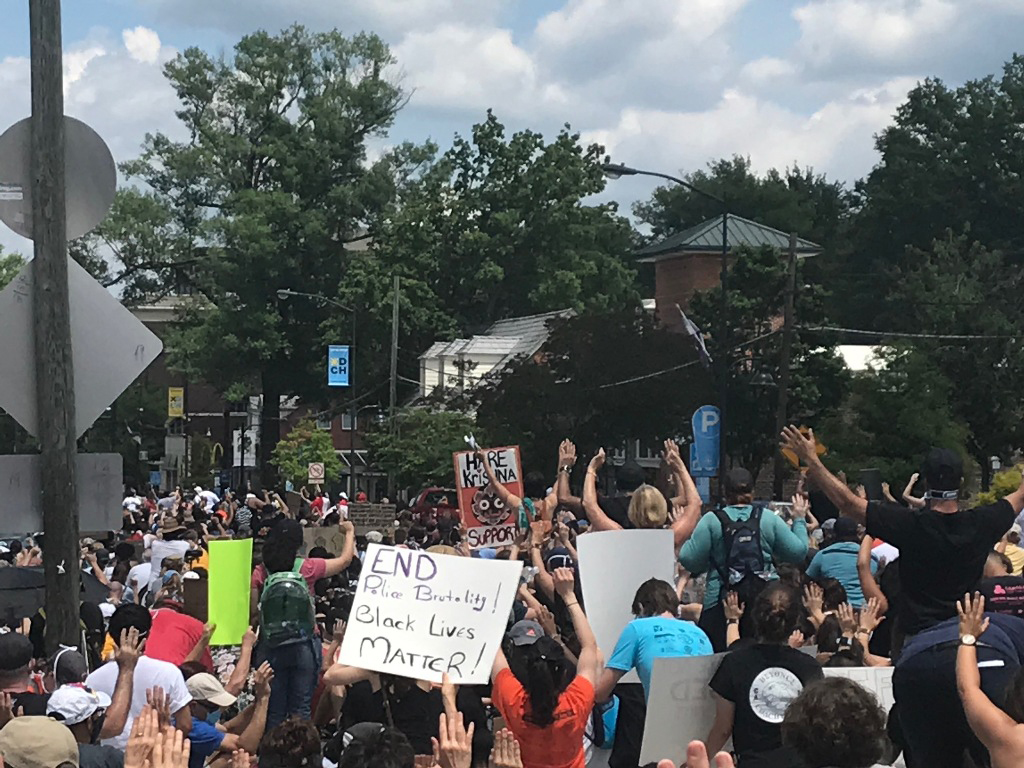

We’re proud of Chapel Hill and Orange County for standing against injustices, calling out racism, demanding change, and proudly proclaiming the Black Lives Matter. Here, some photos from Saturday’s Rally for Justice – and some reminders about the civil rights heroes of our past.

Hundreds of peaceful protesters – most wearing masks – took to the streets of Chapel Hill on Saturday to demand justice for George Floyd and other Black Americans who have recently died following police violence. The Rally for Justice, sponsored by the Chapel Hill-Carrboro Chapter of the NAACP, began at First Baptist Church on North Roberson Street. From there, the crowd proceeded to Peace and Justice Plaza on East Franklin Street.

During the march, protesters knelt on West Franklin Street for eight minutes and 46 seconds, the excruciating length of time a Minneapolis police officer knelt on the neck of George Floyd on May 25 while bystanders took video and begged him to stop.

The Rally for Justice was the second such event in Chapel Hill in two days, following Friday’s rally and march led by UNC Black student groups. A march in Hillsborough also took place on Friday.

Chapel Hill has a long history of fighting for civil rights, including in the 1960s.

In 1960, nine young, Black Chapel Hill men took a stand by sitting down at the Colonial Drug Store. The moment inspired others to fight for civil rights and racial justice. In late February, 60 years later, the town installed an historic marker at 405 West Franklin Street, where the whites-only Colonial Drug Store once stood – and where protestors marched past on Saturday. Today, it is home to the West End Wine Bar. The marker is inscribed with the names of the Chapel Hill Nine – David Mason Jr., Jim Merritt, Clarence Merritt Jr., William Cureton, Albert Williams, John Farrington, Earl Geer, Douglas “Clyde” Perry, and Harold Foster – along with photos from that time period. Durham artist Stephen Hayes designed the marker to rest on a rock base that resembles the low walls of the historically Black Northside neighborhood, where the teenagers grew up.

The marker is one of several ways that Chapel Hill is taking time to reflect on the town’s struggle for civil rights. In early 2020, Chapel Hill Transit transformed three of its most visible downtown bus shelters so that they featured dramatic images of protesters shutting down Franklin Street, picketing, and being arrested by police.

More on Chapel Hill’s civil rights legacy: In 1967, Charlie Scott broke ground by becoming the first Black UNC basketball player and the first Black scholarship athlete at the school. He played for Coach Dean Smith.

In May 1969, Howard Lee became the first African-American mayor elected in Chapel Hill, and the first African-American to be elected mayor of any majority-white Southern town. He won by a narrow margin but was re-elected twice, increasing his vote counts with each election.

Also in 1969, food workers at Lenoir Hall – the majority were Black – went on strike. Thanks to the efforts of the Black Student Movement and several workers, the Lenoir workers received higher pay and better working conditions, in an intersectional quest for racial and labor rights.

UNC was largely built by slaves, including many of its original buildings like Old East and Old West. In the second half of the 20th century, Black students continued to fight for a place on campus to nurture appreciation for Black culture. After the Black Cultural Center was established in July 1988 in the Student Union, students and staff began insisting on a freestanding center. The space was finally built in 2004, named the Stone Center in honor of Sonja Haynes Stone.

Following years of controversy – and more than a century after being erected – protesters toppled Silent Sam in August 2019. Julian Carr’s 1913 dedication speech to the monument proudly shed light on the horrendous treatment of Black people during the Reconstruction and Jim Crow eras.

In a message to the town on June 5, 2020, Mayor Pam Hemminger said, in part: “We share your concerns about how black, brown and any minority people are treated across the country and within our own community. To that end, over the past 10 years, Chapel Hill has instituted and regularly reviewed progressive policies, forged partnerships and invested in community-based programs that help us treat everyone with respect and dignity. … In the days and weeks ahead, please know that we are listening and that we are deeply committed to ensuring public safety, public health, and a community in which all people are free to thrive and to live their lives without fear.”