Almost everybody notices it when they first fly into the area: how stunningly green Orange County is. Pines, oaks, cedars and (much) more.

Yes, the county has grown significantly in recent years, new residential and commercial developments springing up everywhere. But it still remains extraordinarily verdant. Many people here for the first time have the same reaction my nephew’s 7-year-old son had when his family visited a few years ago from arid Arizona.

What impressed him most? “All the trees,” he said. “I’ve never seen so many of them.”

You don’t just notice them at 30,000 feet. Drive west into the center of the historic district of Chapel Hill along Franklin Street. The street — even in the heart of winter — seems protected by a canopy of majestic oaks and other varieties reaching gently from one side to the other.

Around here oaks can seem nearly ubiquitous — red oak, white oak, willow oak and water oak abound. But the area also has a number of other native trees, thanks to good upland soils and rich bottomland: evergreens like loblolly and shortleaf pine as well as eastern red cedar and American holly; hickory species like shagbark, the evocatively named pignut hickory, as well as yellow poplar, sweetgum, sycamore, sassafras, dogwood, persimmon, an assortment of maples.

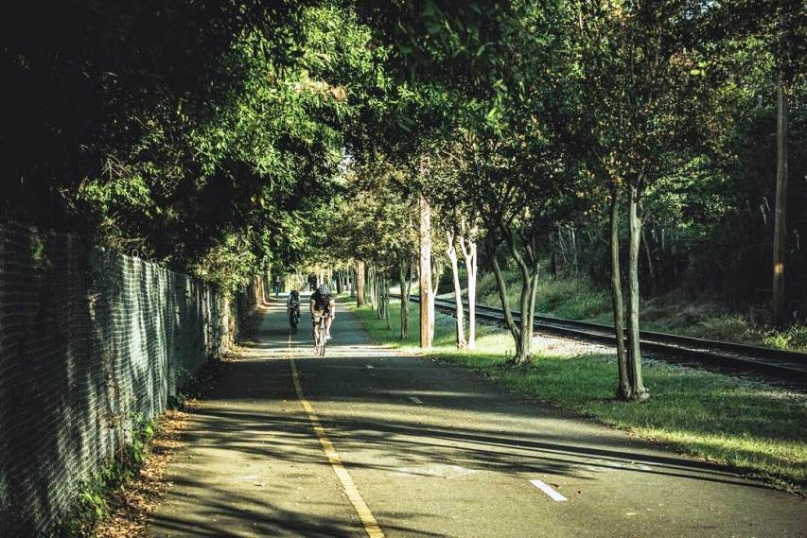

It’s easy to see the wide variety of trees all together in one place at sites like the N.C. Botanical Garden, the Mason Farm Biological Preserve, the university’s Coker Arboretum and along the greenway system in Chapel Hill and Carrboro.

You won’t find, however, many longleaf pine, despite a widespread belief that the longleaf is the official state tree. In fact, the state tree is simply the pine — all eight species native to North Carolina — since it was designated by the legislature in the early 1960s after the Garden Clubs of North Carolina advocated for it.

Longleaf has received the attention because there used to be a lot of them in North Carolina, and it was an important tree in the state’s economy for a long time, explained my friend Rob Shapard, a UNC Chapel Hill lecturer who is working on an environmental history of longleaf pine forests called “A Resinous Land.”

Longleaf is — or more accurately, was, according to Shapard — mainly an eastern North Carolina tree that doesn’t grow naturally far into the Piedmont beyond southeastern Wake County.

But other trees are part of the landscape of this area and part of its history, too. In fact, the area may owe its history to a tree, the Davie Poplar, an enormous tulip poplar in McCorkle Place in the middle of the UNC campus.

According to legend, revolutionary war hero and university founder William Richardson Davie personally chose to locate the school lands around the tree, after having a pleasant summer lunch underneath it. In actual fact, the university's location was chosen by a six-man committee in November 1792 and the tree was named in the late 1800s to commemorate the legend.

But legends live on. The most enduring one associated with the tree is that as long as the Davie Poplar — now more than 300 years old — remains standing, the university will thrive; if it falls, the university will crumble. Consequently, steps have been taken to preserve the tree, including grafting a second Davie, called Junior, and planting a third, naturally called Davie Poplar III, from the original tree’s seeds.

The local commitment to trees has a long history, too. Way back in 1889, cutting down a tree in Chapel Hill was punishable as a misdemeanor and carried a $20 fine. In the 1990s, Chapel Hill adopted one of North Carolina’s first tree protection ordinances. The ordinance calls for a balanced approach to protecting trees without over regulation of residential properties and property owners. Sometimes that approach is tested. Recently many local residents were in a furor over the clear-cutting of trees along Estes Drive, in two places, and also in northern Carrboro, by the Carolina North Forest. In one case, the stand was cut down for development; in the others the property owners said it was to protect the long-term viability of the forest.

Still, despite the loss of those stands, trees continue to flourish here. The university employs a full-time arborist. Carrboro has a Neighborhood Urban Forest Stewardship program. Hillsborough has a Treasure Trees Program designed to recognize and help preserve significant local trees, such as the American beech on East Queen Street and an eastern red cedar between Margaret Lane and West King.

And not surprisingly, Chapel Hill, Carrboro and Hillsborough all have been designated as Tree Cities USA, meaning, among other standards, that they spend at least $2 per capita for the planting and care of trees. And that, of course, they all officially celebrate Arbor Day.

(photo credit: Libba Cotton Bikeway- Ian Garrikson Instagram